Editor’s Note: Last week, Rachel Weiner, a reporter for the Washington Post, was part of the tidal wave of layoffs at the famed newspaper. A fifteen-year veteran of the Post, Rachel has covered a host of topics that touch on the Washington, D.C., area, ranging from local crime to national political news. I first met her nearly a decade ago when we both covered national security trials in the Eastern District of Virginia, but I was merely a visitor coming and going in short increments whenever a certain court case struck my idiosyncratic interests. For years, Rachel was a consistent presence at the Alexandria, Virginia, courthouse, dutifully reporting the daily dockets’ happenings. In this week’s The Rabbit Hole, she takes Court Watch readers through what it means to cover the fastest court district in America. With its storied history, the Eastern District of Virginia, or as it is affectionately known, the Rocket Docket, has seen countless high-profile arrests, indictments, and prominent civil cases. Rachel had a front row seat, albeit from a cramped, windowless office, to it all. – Seamus

When I was offered a job covering the Eastern District of Virginia for the Washington Post in mid-2016, I was warned that it would be “psychologically difficult.” Not because of the subject matter, although I did have trouble sleeping after hearing former Islamic State hostages describe being tortured until they hoped for death. It was the circumstances.

No cellphones are allowed in the Alexandria building, where many of the nation’s most important federal trials took place; there weren’t even lockers in the lobby to hold them. Those who arrived at the courthouse on foot – often because they faced DUI charges that barred them from driving – had to pay a nearby deli to hold their phones or bury the devices in the planters outside the building. If I got an important call or text message during the work day, I wouldn’t know until I made a lunchtime trek to the lot where I parked my car, which served as both transportation and electronics storage. If I didn’t have time for the trip to the lot, about 20 minutes round-trip, I had no way of knowing if someone I agreed to meet for coffee was delayed. I would sit at Starbucks staring out the window like a woman in a romantic comedy from the last millennium.

The Eastern District calls itself the “Rocket Docket,” priding itself on the speed with which the court dispatches cases. A sculpture on the main courthouse in Alexandria bears the slogan, “Justice Delayed is Justice Denied,” beneath a sculpture of a blindfolded Lady Justice atop a tortoise and a hare. The average felony criminal case in the Eastern District of Virginia (EDVA) takes about 7 months from filing to completion, according to federal statistics; in the Southern District of New York, generally viewed as the other preeminent federal court in the country, it’s over 16.

That’s one of the reasons the court handles some of the most significant federal cases in the country. Another is simple geography. It’s where some high-profile defendants live – including James Comey, who the Trump administration has tried to prosecute in EDVA. Prosecutors like bringing cases in a district where jurors are likely to be familiar with and sympathetic towards the government, particularly the national security apparatus. Defendants can be brought to EDVA from overseas via Dulles International Airport, even if they have no connection to the region, such as the British ISIS torturers who haunted me. Having so many national security cases has also led to a large pool of attorneys with the security clearances necessary to represent people in cases involving classified information.

Weiner's Washington Post Press Badge

When I began in Alexandria, the Washington Post was lucky enough to be one of three news organizations with a computer and a landline inside the courthouse’s media room. It was inside a windowless room on the courthouse’s second floor, with just enough space for three desks and a filing cabinet. The only reporters there regularly were Matt Barakat from the Associated Press and me, though someone from NBC News occasionally dropped in. Sometimes I typed there alone in the dark, because the office light went out at 7 pm. When the mother of a member of a white supremacist group told Matt and me in the elevator that we “lived sad lives,” she wasn’t entirely wrong.

Then, former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort was charged with fraud by the special counsel investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election. Chief Judge Leonie M. Brinkema agreed to allow two more news organizations into the space, CNN and Courthouse News, without finding a bigger room. The filing cabinet went. Our desk was swapped for a smaller one (itself a complicated security negotiation). Our printer had to balance precariously on a shelf above my head. If either an AP reporter or a Post reporter wanted to go in or out, the others had to stand up to let us through.

No cellphones also meant no filing from the hallways outside the courthouse. For the Manafort trial, we used a relay system. Two reporters would be in the room to take notes. When something interesting happened, one would peel off and head to the media room to file an update. Whoever was in the room filing would head back to the courtroom, so the person already there could get ready to leave with an update. News organizations that lacked our precious 30 inches of space in the media room devised similar systems that required going outside to assistants waiting with cellphones. For the verdict, some reporters attempted a flag system, holding up to the courthouse windows a green paper for guilty or red for not guilty. The sightlines didn’t work.

When the trial ended, the desks remained, but no other news organization had a reporter devoted to the Eastern District of Virginia. For several years, the Post had not either. Then, in 2013, the Post started reporting on former Virginia governor Robert McDonnell's close relationship with a political donor, which became a federal investigation in the District. McDonnell would be convicted in a trial I helped cover, but the Supreme Court overturned his conviction and raised the bar for what counted as an illegal quid pro quo.

The mundane, nevertheless required procedural steps to cover a federal court.

Despite the isolation and the inconvenience, EDVA was and remains an amazing beat. I got to work with reporters on every desk in the newsroom – national security, business, climate, politics. And it remained a local beat full of quirky local stories that require sustained commitment to find, often about bizarre frauds. I wrote about a con artist who convinced Commanders players she was friends with the Obamas and a Virginia woman who lost the home she’d had designed just for her height to a scam. I was able to interview an anti-gun activist who had been convicted of sending threats to a Republican senator because the defendant happened to be my server at a restaurant in Alexandria. And tips from attorneys often led to my most popular stories, such as one on a challenge to an antiquated Virginia law requiring people to list their race on marriage certificates.

Having a reporter in the courthouse isn’t an unbeatable edge. Attorneys are barred from sharing information under seal, and when it is unsealed, it’s available to everyone in the world via the electronic federal court filing system PACER. Other news organizations paid for tools that flagged new filings; the Post relied on a mix of free tools and our willingness to refresh a page repeatedly. Seamus himself scooped me on the indictment of Julian Assange, which was revealed in an unrelated filing due to a prosecutor’s copy-and-paste error.

But being in the building gave us access to and an understanding of the players in some of the biggest legal and political stories of the past decade. Early in my tenure, President Trump unexpectedly promoted EDVA U.S. Attorney Dana Boente as acting attorney general. Boente went on to be ousted from the Trump administration in 2020 for his involvement in the investigation of Michael Flynn, which I covered. (In fact, I had a leg up on the news that something had gone wrong with Flynn’s deal to testify against a former business partner because I spotted him at the Starbucks near the courthouse, unexpectedly).

Many of the assistant U.S. attorneys who have been pushed out or resigned from the Justice Department in recent weeks are all familiar to me from covering EDVA, as is the judge who oversaw the aborted prosecution of James Comey. At a time of unprecedented threats to and attacks on the justice system, it helps to understand those involved as human beings. That’s only more crucial as many of them are choosing to be fired rather than follow the edicts of an administration defying long-held judicial precedent and orders.

"I haven’t really gone back to talk to any of the old line prosecutors I’ve known for decades to ask how they feel about what’s happened to their office. I’m pretty sure I know," Barakat, who covered Northern Virginia for 25 years, said in a text message. "With very few exceptions, the lawyers in the US attorney's office relished their ability to pursue justice without political interference, and gladly accepted the smaller spotlight that accompanied their work as a result. The collapse of that ethos would be a hell of a story. But AP never replaced me, and after the bloodbath at the Post, I just don’t think anyone’s there any more to report it."

While spending countless hours in that windowless room in Alexandria didn’t help me break the Assange story, it did help me and my successor, Sal Rizzo, write the definitive account of how and why the deal was made. I was able to dig deep on the effort to cut the sentence of a man who, before that happened, killed himself in prison, and on disagreements between American and European prosecutors over terrorism cases.

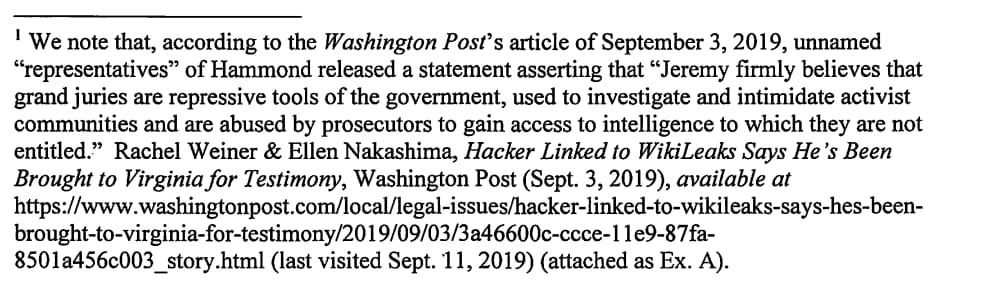

EDVA prosecutors and defense attorneys frequently cited Weiner's Washington Post coverage in motions to judges. (U.S. v. John Doe, 1:19-dm-00050)

Sal took over my old beat in Virginia when I moved to covering the D.C. Circuit and Fourth Circuit in 2022. When I started on the Metro desk in 2014, I was the reporter for the Arlington and Alexandria local courts, and another for the federal courthouse. They combined those jobs then, which made sense given our resources. But since then, the cuts have been far deeper, and each one has meant both less local coverage and less texture and nuance in our national coverage. Relying on reporters with no knowledge of the legal system can lead to mistakes or misinterpretations, as when we suggested “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh’s early release from prison was a surprise rather than a standard benefit for any prisoner with a record of good behavior.

“To fully understand a case requires more than just a quick scan of a government press release. Quality journalism involves combing through pleadings, sitting in court hearings, and interviewing individuals,” said defense attorney Jessica Carmichael. She represented one of the first defendants I covered in EDVA, a young guy from Northern Virginia who joined and then immediately fled the Islamic State in Iraq. “Of course, this takes time that reporters will not have if they are stretched too thin.”

Defense attorneys and prosecutors rarely agree on much, but there is a consensus that consistent presence at a courthouse is important for nuanced and comprehensive legal reporting.

“Folks who come in for some huge event, they're not going to know the characters, the players, they’re not gonna know the rhythm of the courthouse,” said Dennis Fitzpatrick, who prosecuted the ISIS hostage takers as an Assistant U.S. Attorney. “Someone who just parachutes in isn't going to have the full story.”

Between buyouts at the Post last year and the layoffs this month, the Post eliminated all our local courts journalists save Sal. We no longer have a reporter in D.C. Superior Court, where most crime in the city is prosecuted. We don’t have a full-time reporter on my old beat covering the appellate courts, where some of the most significant challenges to Trump’s policies are being heard.

We no longer have the reporters with whom I helped chronicle the Jan. 6 prosecutions, as the Justice Department attempts to rewrite that history, and some of those defendants are arrested on other charges. (Our local reporter who covered extremism, including the fallout from Jan. 6, was also laid off last week). We have fewer people covering courts at all, even as the administration’s ‘campaigns of retribution’ against enemies and deportation both run through them.

One of my regrets is that we failed to mark the death of the brilliant, cantankerous Judge T. S. Ellis III, who became nationally famous – and controversial – for his handling of the Manafort trial. But continuous cuts over the past few years as the Post lost money slashed our Metro staff from nearly 90 staffers to under 50, even before this month’s gutting. Our obituaries staff had been cut to one person, whom I asked if I could write the story. But I had moved on to another beat doing what an entire team had previously covered, and didn’t have the time. (We now have no local or national transportation reporter, the beat I moved to after leaving court coverage).

In all, we lost 18 local reporters and 7 local editors in these layoffs; five of the 16 remaining reporters are being transferred to national politics and criminal justice coverage. (Two of those left are on fellowships and may not have jobs at the end). I hope some of that coverage will include what happens in the Eastern District of Virigina. If it does, one thing has changed that might help a Post reporter juggling several courts at once.

Last year, the Rocket Docket began allowing cellphones to be stored in the courthouse lobby.

-30-

This piece is part of our weekly Sunday Series we call The Rabbit Hole where we choose a single federal court docket, filing, or topic and dive deep into the details. You can read past issues on topics ranging from News Deserts to the lack of consistent funding for court-appointed defense attorneys on our site.

If you are reading Court Watch for the first time here or you were forwarded the piece, you can subscribe here to get our free weekly Friday roundup of federal court documents in your inbox and our member-supported Rabbit Hole every Sunday.

Finally, if you’d like to support independent journalism like this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.