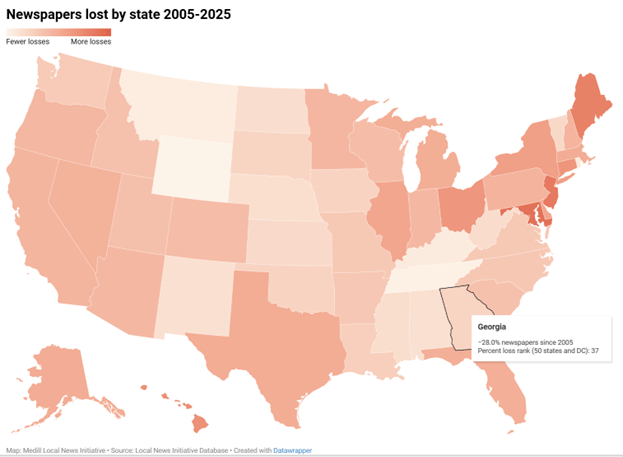

Editor’s Note: The Middle District of Georgia is filled with rich news stories that even a few years ago would have been quickly reported. But it now sits in a so-called ‘news desert’, a place that is largely devoid of even a single newspaper, let alone a reporter dedicated to its federal court. In this week’s The Rabbit Hole, Peter Beck seeks, at least temporarily, to fix that by highlighting all the newly filed court dockets in that district that the public missed because of the quickly diminishing number of local journalists. Given the thrust of this piece, this edition of The Rabbit Hole is not behind our usual paywall. If you’d like to support this type of reporting, please consider a paid subscription. - Seamus

A car crash with a U.S. Postal Service mail carrier, prison civil rights suits, a small local music venue being sued by a major music company, and an arrest on a U.S. Army base—these are all cases filed in the past week in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia that went unreported. They are all part of a broader trend of the death of local news, leaving community members uninformed about important developments in their neighborhoods and leading to less and less transparency in the legal system.

Georgia’s Middle District stretches from the southwest corner of the state all the way up to its border with neighboring South Carolina, where Clemson University is located nearby. The District covers 70 counties, with its headquarters in Macon and courthouses in five counties. Established in 1926, the District sits below Georgia’s Northern District, which covers Atlanta, and above its Southern District, which encompasses Savannah, Augusta, and the rest of the Georgia coastline. Its four active and two senior district court judges are an even number of appointments by democratic and republican presidents.

Legal developments—be they in criminal or civil cases—are a revealing window into what happens in a community. For instance, a docket from a case in Fort Benning, one of the largest U.S. Army bases in the continental United States, alleges that a soldier overpowered a person to take control of a vehicle and then refused to allow them to call 911. In Athens, a Black worker at a glass company reports he was forced out after his boss repeatedly called him the n-word. A woman from Decatur is suing a debt collector and a tow truck company after an encounter that reportedly left a tow truck driver in the back of a police car when they tried to tow her 2015 Volkswagen Tiguan without a warrant. Similarly, a man from Oconee says a consumer reporting agency is misreporting $10,000 as money he owes. And in Macon, a former FedEx driver is suing to return to his old job after allegedly turning in his supervisor for harassment.

None of these cases filed this week were picked up by local news, and there’s a clear reason why: Among the 17 counties in Georgia that don’t have a news source, 12 of the counties are in the Middle District’s jurisdiction. Out of the 70 counties that fall in the District, only nine counties have more than a single news source. There simply wasn’t anyone there to investigate and report what was happening. It’s unsurprising within the national context: According to the Local News Initiative at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, almost 40% of all local newspapers in the U.S. have vanished in the past two decades, leaving at least 88 million people with near-zero or no access altogether to reliable local reporting. That’s one in four Americans.

In 2005, there were 150 counties in the U.S. without a local news source, a number that’s climbed to 212 today. Among all newspapers, 148 went under in 2024 alone, the year with the most recent data available, because of closures or mergers into larger corporations, which often coincide with layoffs and cuts in reporting coverage. The result is that areas home to millions of people, like the Middle District of Georgia, don’t have access to trustworthy basic information about what’s going on in their backyard. This information deficit is compounded by the fact that the court records are behind a government-mandated paywall, making access even more difficult for the masses. All told, the dockets and their associated court documents for this piece cost $53.80 in PACER fees for Court Watch to obtain. But fees alone don’t uncover the news. It requires a reporter to call plaintiffs and defendants and draft the story. Then an editor to review, and a platform to publish. All things that are in short supply in the Middle District of Georgia.

When reporters aren’t around to watch what goes on in federal courts, local communities are impacted. Pals Watering Hole is a rustic, small music venue located in Eatonton, Georgia, in a rural county called Putnam between Athens and Atlanta. On January 26, just two weeks shy of the bar’s 4th anniversary of being open, the Watering Hole and its two co-owners were sued by Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), a major license fee collector for musicians. The civil suit alleges that Pals Watering Hole played four songs in BMI’s repertoire, violating copyright protections. Those songs include such classics as Hank Williams Jr.’s ‘Family Tradition’ and Queen’s ‘Another One Bites the Dust.’

The case potentially opens up Pals Watering Hole to thousands of dollars in damages and even more in attorneys’ fees to defend against the suit. In the past, public reporting has deterred major companies, including BMI, from filing copyright claims against smaller venues, perhaps keeping in mind that it would be bad publicity for them to pick on “the little guy.” In September 2024, when BMI sued an Irish pub in Tennessee for allegedly playing Dolly Parton’s ‘I Will Always Love You,’ Court Watch’s inquiries led BMI to withdraw its complaint against the pub. A publicist for Parton went on record then, “Dolly did NOT file this lawsuit—BMI did.” In the Middle District of Georgia, there are few reporters left to shine a light on the lawsuits targeting family restaurants by multi-million-dollar out-of-state companies.

Another example of a case that wasn’t reported but could have been used to raise awareness and support comes from an insurance case in Putnam County, where a couple’s home burned down, reportedly because a defective air fryer caught on fire. The suit alleges that the company, Atekcity, had issued a recall for its Cosori air fryers but failed to adequately alert customers of the safety concern. The recall impacted two million air fryers, meaning local news coverage could have alerted other customers nearby to the fire risk or, at the very least, increased the public’s mindfulness about product recalls.

The Middle District’s docket also tells stories about the most vulnerable members of communities and the ways society treats them. On Thursday, January 29, a man who’s confined to a wheelchair sued the management operator behind the Athens West Shopping Center, alleging that seven businesses are not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The man’s civil complaint described how everything from the mall’s parking lot to its bathrooms is inaccessible to him and other disabled people. The case has gone unreported until now, but yet again, a local reporter monitoring the docket could have investigated to better understand the root of the problem.

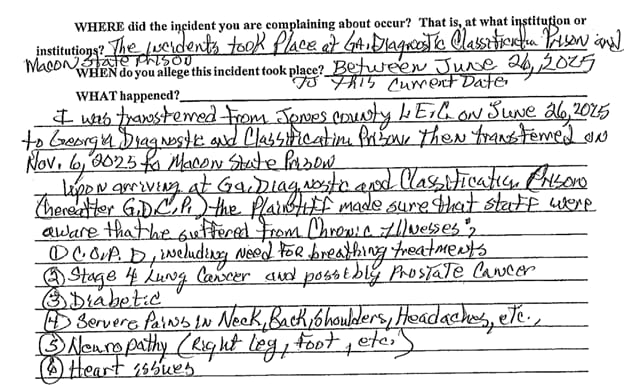

Georgia’s six most populous state prisons all fall in the Middle District, leading the District’s judges to hear many of the prison civil rights suits and habeas petitions coming out of Georgia. In just the final week of January 2026, six cases were filed by people incarcerated in the District, including one by Ernest Howard, who is serving a life sentence on a 1987 conviction for rape and kidnapping. In his pro se petition, the now 62-year-old Howard says he is suffering from Stage 4 lung cancer and other serious ailments that affect his breathing.

Civil complaint, Ernest Howard v. Warden Sampson, MDGA

Writing to the court, Howard asked a judge to intervene and order Georgia prison officials to house him in a cell where he could be away from tobacco and other smoke emitted by prisoners, citing the smoke’s severe impact on his health conditions. Smoking is prohibited in state prisons under Georgia Department of Corrections’ policy. Yet Howard described in his petition multiple pleas to prison officials to transfer him away from the cell he reportedly shared with an inmate who was a heavy smoker. Howard wrote that prison officials responded to him by threatening retaliation, allegedly proposing to place him in a 24-hour lockdown until his death from Stage 4 lung cancer rather than move him to a smoke-free cell block.

Howard’s case went unreported and thus has not been investigated for its veracity or publicized in a manner that could draw the attention of potential pro bono local lawyers. Neither were the recently reopened case of a woman who claims local police planted drugs on her, an incarcerated man who says he has been in solitary confinement without any dedicated time for physical activity for over a year, nor another man’s case who alleges he warned prison officials before being stabbed, among the countless other civil rights cases filed before this week that will never be reported.

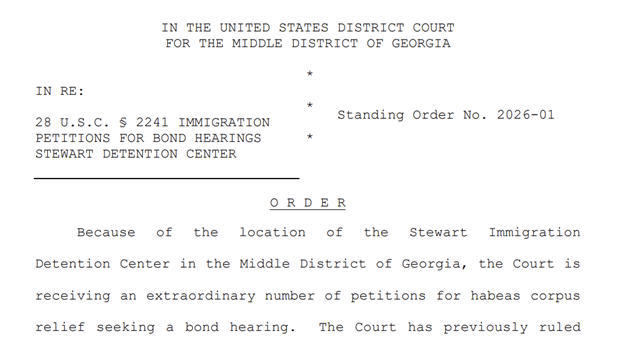

In the southwest corner of the state, right over the border from Alabama, is the Stewart Detention Center, a private prison operating as one of the busiest immigration facilities in the U.S. Since last Sunday, 43 habeas corpus petitions have been filed by individuals detained at the detention center.

On January 29, Judge Clay Land issued a standing order regarding the “extraordinary number of petitions” in the Middle District, writing that “despite these clear and definitive rulings,” requiring bond hearings for detained migrants, “the Government refuses to provide bond hearings to persons who fall within the parameters of the Court’s rulings in J.A.M. and P.R.S. [a past order that ruled people detained at Stewart “are entitled to relief”] unless the Court orders the Government to do so in each individual case. The volume of these petitions has created an administrative judicial emergency which requires the Court to consider novel solutions to assure that these cases are handled expeditiously.”

Jan 29, 2026 Standing Order, MDGA

Court Watch, however, was unable to review the 43 habeas petitions, which, by virtue of the sensitive, personally identifiable nature of those filings, are not available on PACER. Neither is the underlying criminal complaint for the immigration defendant’s arrest. To understand these people’s pleas or why the government might want them detained, a local reporter would have to travel to the courthouse for a physical copy. Given the state of journalism coverage in the Middle District of Georgia, that appears increasingly unlikely.

The Middle District of Georgia is by no means an outlier. There are dozens of other federal court districts around the country that lack well-resourced newsrooms and dedicated legal reporters. The solution can not be a three-year-old news startup, such as Court Watch, briefly devoting 2,000 words to a district that deserves much more sustained local coverage.

Much like Judge Land’s habeas order, our communities are experiencing a reporting emergency, one that will also require the consideration of novel solutions. To do otherwise would leave this and other news deserts with a public left less informed, and countless stories in the dockets left to die in the darkness.